Fallen But Never Forgotten

After 76 years, a missing Regis soldier comes home

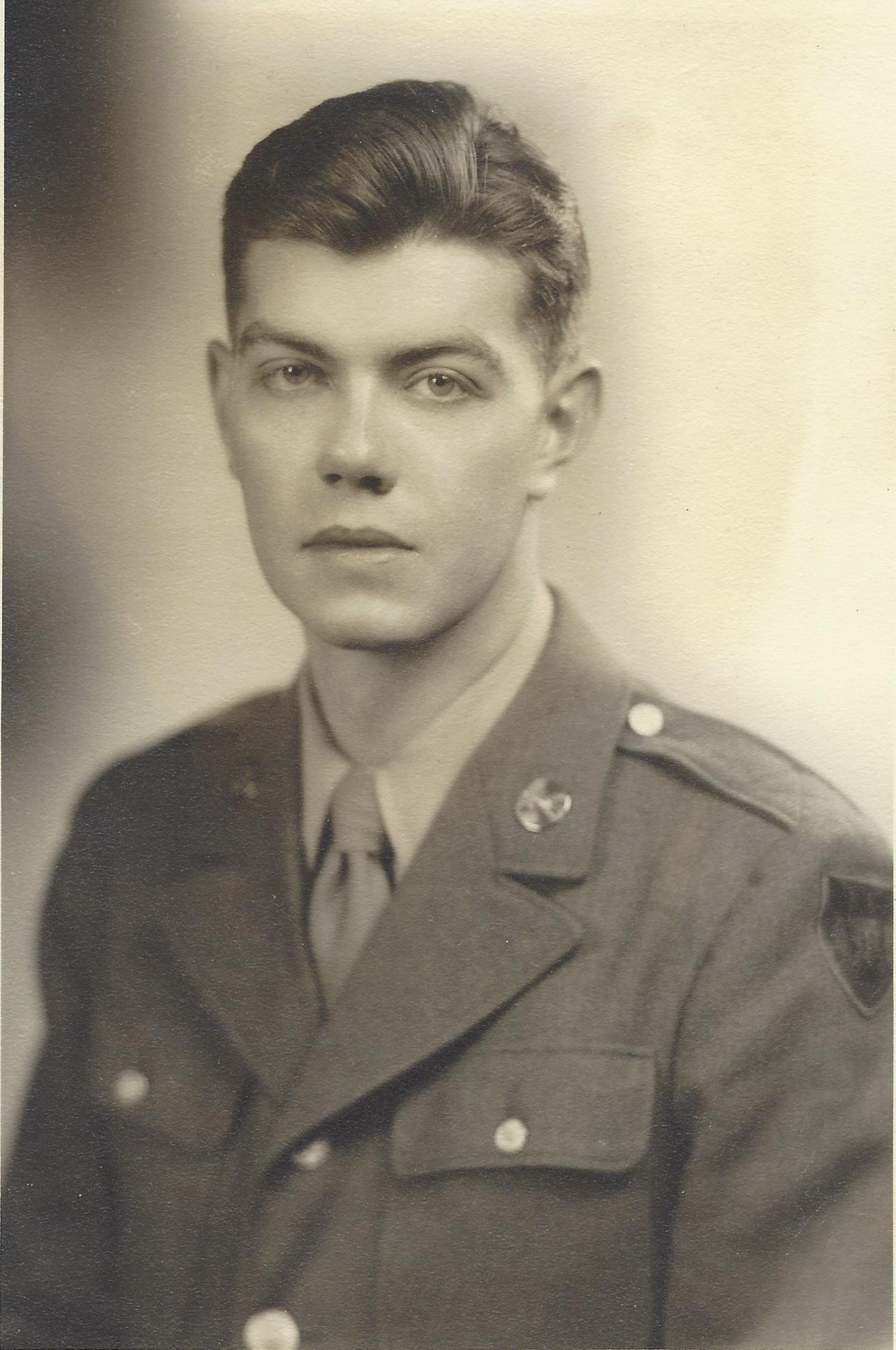

Harry Wilder was 21 years old when he graduated from Regis College in the summer of 1943. Immediately after graduation, like many of his generation, he went to war.

Harry Wilder was 21 years old when he graduated from Regis College in the summer of 1943. Immediately after graduation, like many of his generation, he went to war.

Wilder never returned to Regis, nor to Colorado. He never again saw the sunset over the Rockies, walked the corridors of Main Hall or celebrated with friends. After he proudly wore his graduation cap and gown, Wilder enlisted in the Army to serve in World War II. He was killed in action in November of 1944.

It took more than 75 years to bring his body home.

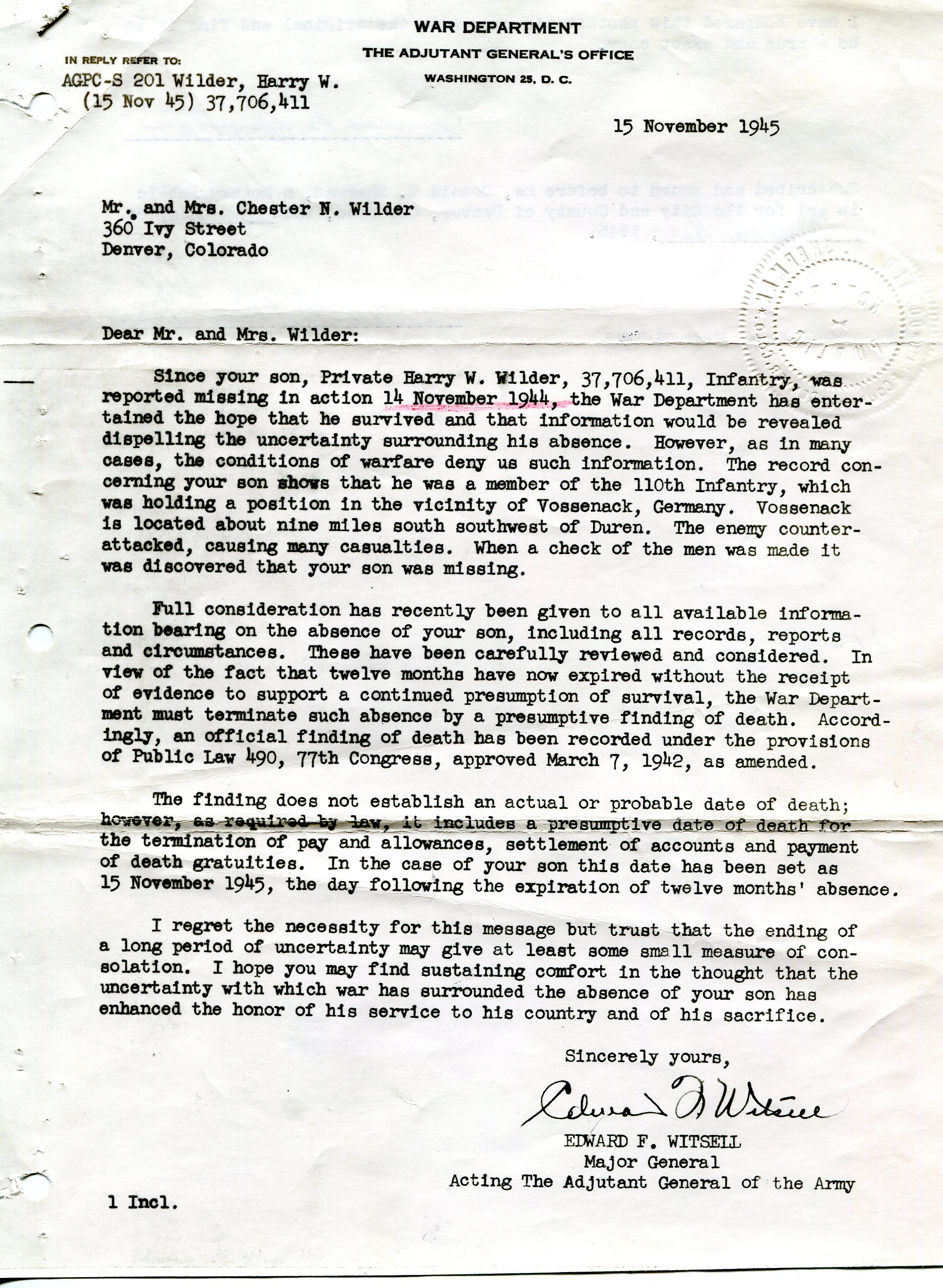

Initially, Wilder was declared missing in action in November 1944. A year later, the Army notified Chester and Edith Wilder that their only son had been declared dead.

Wilder’s body was not found. His parents and younger sister, Leonor “Jane” Wilder, were not able to bury him, or to learn what had happened to their son and brother. In time, Jane Wilder grew up and had a family of her own. She often told her children the story of her older brother.

His family didn’t know that three years after his death, Harry Wilder’s remains were discovered near the Hürtgen Forest where he was killed. They could not have foreseen that nearly 76 years later, the son and brother they lost would receive a hero’s burial in the nation’s most sacred ground: Arlington National Cemetery.

Harry Wilder at Regis: Class President and Editor

It was the summer of 1941 when Wilder transferred from one Jesuit institution, Loyola College in Baltimore, to another: Regis College, as Regis University was called then. Wilder’s father worked for the Montgomery Ward department store and moved the family to Denver in June 1941. Harry Wilder, who was in a Baltimore hospital recovering from a back injury after a toboggan accident, followed soon afterward.

Wilder’s mother Edith wrote, “While in his last part of his Freshman year, he [Harry] fell from a toboggan and hurt his back ... In June that year, we moved back to Den- ver. Harry stayed with the Jesuits and made up his loss while in hospital, following us to Denver in August ... He started back to Regis College with all the honors and high marks.”

Immediately upon arriving at Regis College, Wilder began to play an active role in student life. During his junior year, he was associate editor of the student newspaper, the “Brown & Gold.”

Wilder was a Biology major with a minor in Chemistry and hoped to study medicine after graduation. He was dedicated to his extracurricular activities despite his demanding course schedule.

In addition to being appointed editor of the “Brown & Gold” his senior year, Wilder was elected president of his senior class.

He was a member of a sodality — a Catholic fraternal association — and they had taken on the project of purchasing a plaque honoring Regis students and alumni serving in WWII. Wilder sat on committees to organize dances and writing contests between the men of Regis and the women of Loretto Heights College. He was a member of the International Relations Club. In 1943 he represented Regis at the Annual Intercollegiate Legislative Assembly at the Colorado statehouse. And he tied for second place as the Best Dressed student at Regis College.

Before his graduation, the student newspaper wrote, “In his two years at Regis, Harry has become one of the best-known and best-liked men on the campus. His participation in school activities is legion.”

The War in Europe

That summer, immediately following graduation, Wilder enlisted in the Army and signed up for the Advanced Service Training Program (ASTP). The program would have allowed him to study medicine after basic training and enter the war as a medic. Unfortunately, by the time he completed basic training, the military had canceled the ASTP, and Wilder was reassigned to the infantry. He was ordered to the European Theater of Operations.

Wilder sailed to Scotland in September 1944. In his letters home, he told of dancing with English girls, practicing his French, attending Mass and exchanging ammunition until all his bullets said “made in Denver” – signifying that they were made at the Denver Ordinance Plant, which was actually located in Lakewood.

On Friday, October 13, 1944, Wilder landed in Normandy, France. Three days later he wrote to his father:

“Hello Chief! The muddy beaches of Normandy extended a cold greeting to us on the unlucky Friday. Unlucky it was too in view of the fact that all our packs with our personal belongings were lost en route and apparently they never will catch up with us. Outside of my equipment, the only thing I lost was my writing kit, with my pictures and address book. I felt rather bad about it, but I saw several white crosses where some of the boys had lost considerably more ...”

Wilder made his way through France to Germany where he was assigned to Company B, 1st Battalion, 110th Infantry Regiment, 28th Division, while it was recuperating from fighting at the front.

The Fighting Tenth, as it was known, had been in the thick of the battle for the Hürtgen Forest near Germany’s border with Belgium. Shortly after Wilder joined his new unit, it was ordered back to the front line.

The Colorado and Baltimore winters Wilder was used to did not prepare him for the November winter and the dense forest landscape in which he found himself. The unfamiliar terrain and the ground solid with frost proved formidable foes. The German army was too familiar with the terrain and unfortunately, due to the overwhelming number of German forces, many dead Americans were left where they had fallen in the undergrowth and on minefields.

After stopping a fierce German counterattack, the Fighting Tenth was withdrawn from the front on November 15, 1944. Wilder was not with them.

Bad News Comes to Ivy Street

In the late fall of 1944, Chester Wilder had mailed his son a letter in which he reminisced about his own service in the trenches during World War I. Chester Wilder wished his son a pleasant Thanksgiving and said he looked forward to future Thanksgivings when the family would celebrate together.

Chester Wilder’s letter was returned, marked undeliverable.

On December 1, 1944, there was a knock on the door of the Wilders’ home on Ivy Street in Denver. A Western Union telegram reported that Harry Wilder was missing in action. The language was brief and offered little detail.

In March 1945, another telegram was delivered. It stated that Harry Wilder’s last known whereabouts were “Near Vossenack, Germany. A check of PVT Wilder’s organization was made after a strong enemy attack, and he was missing.”

On November 14, 1945, exactly one year to the day that Wilder was reported missing, as was public law at that time, the Army told his parents that Pvt. Harry W. Wilder was now classified as dead.

After the war, Wilder’s name was memorialized on the Walls of the Missing at the American Cemetery in Margraten, Netherlands. His body may have been lost, but his memory lived in the hearts and minds of his family and friends.

Regis Memorial

In 1948 Wilder’s parents visited Regis College to present a plaque honoring Harry and the 28 other Regis students who lost their lives during World War II. The plaque now is on display on the west side of the third floor in Main Hall.

After the war, Wilder’s sister Jane grew up, married, William “Bill” Prindiville and had three children, all girls: Sharon, Sheila and Eileen.

“Growing up, Harry was always with us,” said Sheila Prindiville, who lives in Washington, D.C. Prindiville is a physician — as her Uncle Harry hoped to be — and works with the National Cancer Institute.

“My mother celebrated his birthday, and being a Catholic family, we would always make sure there were memorial masses for Harry.”

“His story was often told at family gatherings and growing up, he was present in our lives. My parents would often take out the letters he sent from Europe and read them to my sisters and me,” Prindiville said. “Although my mother was young when Harry left for Europe, she made sure our family remembered her older brother.”

Not knowing for certain what happened to Wilder added to his family’s pain. Prindiville recalled that, as a child, she would wonder whether he had hit his head and was lying in a hospital in Europe, not knowing who he was.

Harry Remembered: Stories from Wartime

When Professor Ronald Brockway and Professor Dan Clayton, along with the Rev. Jim Guyer, S.J., started the Stories from Wartime lecture series at Regis in 1995, they began interviewing veterans and collecting memorabilia that connected World War II to Regis University.

Bill Prindiville visited the Northwest Denver campus in 1997. Despite never having met Harry Wilder, Prindiville wanted to preserve his brother-in-law’s memory, so he and the family donated Wilder’s correspondence, his Purple Heart and his Regis diploma to the University’s Stories from Wartime archive.

“Harry’s story is special for the students because here was someone who was like them — an active member of the Regis community struggling to balance extracurricular activities with the challenges of academic learning,” Brockway said. “They responded to the fact that Harry attended classes in Main Hall, stayed in Carroll Hall when it was the college dorm, socialized in the Quad, and walked in the same Berkeley neighborhood that they do.”

Dr. Brockway noted that Wilder’s story became a fixture in the Stories from Wartime series. Harry’s story was unique. It was about a person who would forever be a young adult like they were at the time they heard his story. Harry Wilder emerged from a handful of artifacts – his letters, photos and medals plus several cold, impersonal, official documents. It was a story of human tragedy – of a life lost and the lasting impact on his parents and his sister,” Brockway said.

Identification and, Finally, Burial

No one in the family knew that in 1947, two years after the war ended, a German woodcutter from the village of Simonskall near Hürtgen Forest found several human remains scattered across an area of woodland. The remains were skeletonized but not buried and there were no means of individual identification.

The U.S. Army collected the remains and concluded that the individuals had likely been killed by artillery fire.

A crucifix was found with one set of the remains, and on April 13, 1950, the remains were interred at the U.S. Military Cemetery in Belgium.

They remained there, untouched and unidentified until 2018.

The Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency (DPAA) was established in 2015 to identify the remains of the fallen across all conflicts involving U.S. servicemen and women. Its mission is to provide the “fullest possible accounting for our missing personnel to their families and the nation.” The DPAA provides background on battles and tries to reunite loved ones with the remains of the fallen.

In 2017, the DPAA contacted Harry Wilder’s family to discuss its mission and invited them to donate DNA. Wilder’s eldest niece, Sharon Hillman, provided a DNA sample, which enabled the DPAA to search for a match among the unidentified remains in their archive.

In November 2018, the DPAA contacted the family to say they were certain they had found a match. They met with the family in Chicago in May 2019 to discuss their findings. DNA extracted from the remains the woodcutter had found in Simonskall in 1947 had a strong match with the sample provided by Sharon Hillman. The DNA, combined with the height, partial dental records and the crucifix, led the DPAA to confidently say that one set of the remains were those of Pvt. Harry W. Wilder.

Wilder was no longer lost. “There was a sense of relief when we were contacted. My father [Bill Prindiville] couldn’t believe it. He nearly asked the military to double-check and make sure it was him,” Sheila Prindiville said.

On February 28, 2020, Harry Wilder’s remains arrived in Washington, D.C. On March 4, he was laid to rest in Arlington National Cemetery with full military honors. Wilder has now returned to the United States of America, the country he loved and the country he served.

His remaining family – his nieces, Sharon Hillman, Sheila Prindiville and Eileen Hafner – attended the ceremony with their own children to remember and honor the relative they never met but who remained present in their lives. Bill Prindiville, who had worked for years to keep his brother-in-law’s memory alive, did not get to see Harry return home to a permanent rest; he died in January 2019. His wife, Wilder’s sister Jane, had passed away in 1985.

“It was an emotional day that brought us a sense of closure to Harry’s story. The military did a fantastic job honoring their fallen brother. From the initial contact they made with us back in 2017 right through to the end, they have been by our side. They have been by Harry’s side for 74 years,” Sheila Prindiville said.

When asked about Wilder’s legacy, Brockway said: “I’ve been telling Harry’s story for over two decades and keeping his memory alive for our Stories from Wartime students. But it wasn’t until 2020, 75 years after the end of World War II and 23 years after I started talking about Harry, that I am able to say: Harry has been found and he is home at last.”

The Battle for the Hürtgen Forest

It has been all but forgotten now – overshadowed by the decisive Battle of the Bulge, which partially coincided with it.

But the battle of the Hürtgen Forest, in which Harry Wilder was killed, was the longest single battle on German ground during World War II. It also was among the most costly: Between September 19 and December 16, 1944, as many as 33,000 American soldiers lost their lives.

Hürtgen Forest is 10 miles from Germany’s border with Belgium. It’s a rich, dense wood where sunlight struggles to reach the forest floor. During the war, the thick woods limited visibility, and travel through the forest was difficult because there were few decent roads. Stephen Ambrose in his book “Citizen Soldiers” said those who were there described the forest as “a green cave, always dripping water, low roofed and forbidding.”

It was not a place for combat.

The German infantry defended the forest because it offered access to the Roer River dams and the ability to reinforce other battalions. The Allies wanted to take the forest because they wanted to prevent the German army from releasing the water in the reservoirs. If released, the water would swamp any forces operating downstream and slow the Allies’ advancement through Europe.

The dense forest made air support impractical, and mortars were high-risk because when fired, they would explode in the treetops, raining shrapnel on the troops below.

In December, after three months of fighting, U.S. troops were still pushing their way through the difficult terrain when the German army launched an offensive in the Ardennes forest. The German move — which ultimately led to the Battle of the Bulge — caught the Americans off guard, and brought the fighting in Hürtgen Forest to an end.

Header photo by Brett Stakelin; other photos courtesy Wilder/Prindiville families unless otherwise noted.